The possible travels of the Santubong Buddha

Buddhism is one of the world’s largest religions and was established in India around 450 BCE. It spread throughout China, Korea and Japan, followed by incursions into Southeast Asia. In this essay, we attempt to trace the image of the Santubong Buddha located in the Borneo Cultural Museum.

Early Buddhist relics depict places of sacred sites. For example, empty thrones, trees, wheels, animals, plants, nature and spirits adorn the earliest representations. The three ladders at the holy site of Sankasya show where the Buddha descended from heaven.

The image of Buddha was the subject of debate. European scholars felt the image was taken from the Greek invaders and then transferred to the Buddha. Ananda Coomaraswamy in 1927 felt the images were of Indian origin and did not copy the statues of Apollo and other Greek deities. Coomaraswamy opinion held that “Greek art was unjustifiably exaggerated because of the prejudiced view of European scholars”. His opinion, that the Buddha was of Indian origin and not Greek, holds sway until today.

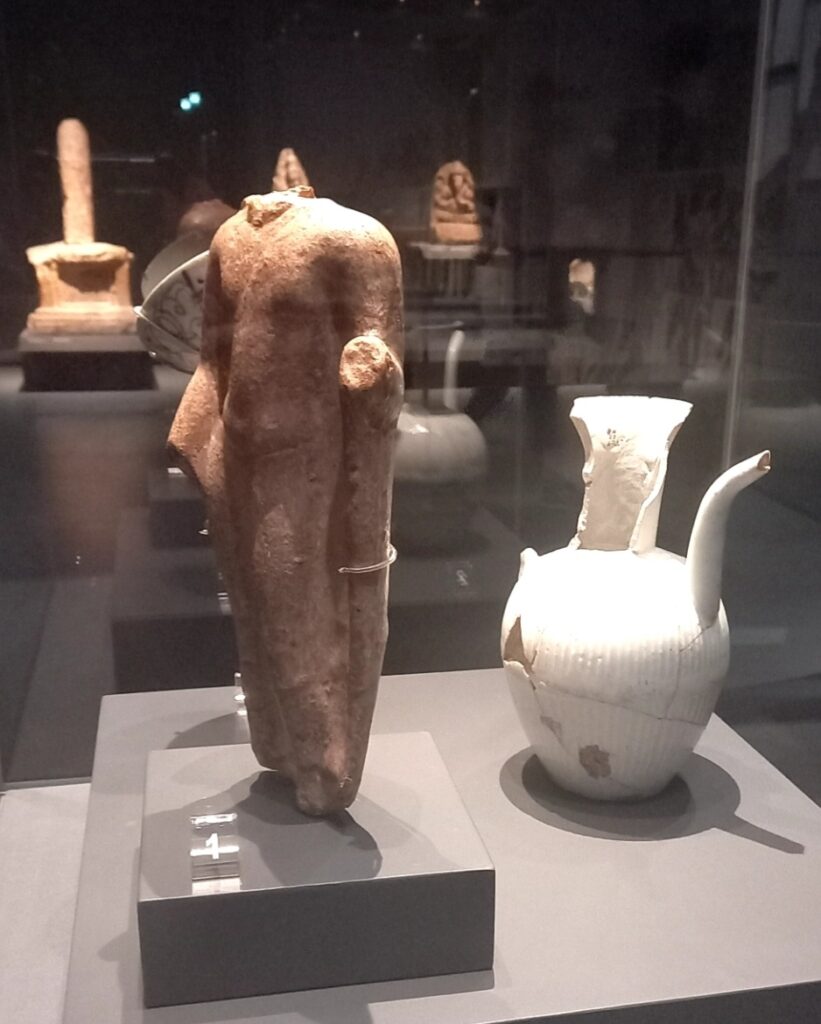

The next advancement in the construction of the Buddha deity occurred in the cities of Gandhara or Mathura around the first few centuries of the Christian era. The Mathura Buddha was carved in red or rose-hue sandstone. The image was marked with spots or smears.

In the Mathura sect, the headgear of the Malays can be plainly seen on the Buddha. However, the cap could designate a well-rounded head, someone destined to wear a turban or a spiral. Because not many of these Buddhas were found, it was thought the images were made from wood or clay because they disintegrated and very few have been found.

The Gandhara Buddha image had delicate facial features, detailed folds in the cloth and sometimes a halo behind the head. Seated, the hands were sometimes folded in the lap, one folded in the lap while the other hung downward or both hands crossed across the heart. The Gandhara Buddha spread throughout Asia.

In the Gupta period, (4-6 century AD) the Mathura Buddhist image changed towards a more lady-like likeness. Here, the image shifts from “a strongly masculine to an overly female image.” Within this shift at the city of Sarnath, the Buddha changes from a tense image to a slackening of the muscles around 380-410. The folds in the robe have been smoothed out. All the folds have been removed 50–75 years later by 485. The eyes have become downcast and the genitals no longer show through the robe.

The body also changes. The Mathura body becomes elongated, but the shoulders remain rather massive with expansive, powerful shoulders, thick waists and small heads. The breasts are softer and rounder. The weight is shifted from one leg and the knee is slightly bent. The genitals have been removed, possibly because of the celibacy of the Buddha.

According to Tom Harrisson, the totally discredited curator of the Sarawak Museum, the type of Buddhism associated with the Santubong was tantric. The idea of tantric Buddhism making its way to Santubong is absurd. There is no information that this form of disgusting Buddhism has ever made its way to Santubong. None of the histories of the Bidayuh or Chinese even suggest of the sexual nature of this type of religion.

According to the museum, the statute was constructed during the Gupta Period and, if I may add in, the Mathura design. We have discarded the idea that it was Tantric because we cannot trace any depravity among the Bidayuh or Chinese that would show Tantric philosophy.

The pilgrimage of the people visiting India was a long one. They began by walking from China over to India and then south to Sri Lanka for the return sea voyage to China. One pilgrim counted 13 years before his return voyage to China. He carried 176 lontar leaf scrolls, plus sacred images. One can only assume that one of the sacred images was the Santubong Buddha. On another account, the name of Santubong at the time was Po’ni and there are many towns and villages in India that have the prefix of “Po”.

The most likely route the Buddha travel was from India, to Ceylon, down the island of Sumatra and across to Santubong. During the route, pilgrims from India returning to China could have carried the Buddha to Santubong.

The Kingdom of Tanjungpura was also formed during the Majapahit Empire. Located in southwest Borneo, it could have possibly connected to Santubong.

According to oral history, Hyang Gi came from Tanjungpura and established a kingdom in Santubong in ~966. In the succession of names, they all seem to follow the Buddhist tradition. For example, “Saganda” is from the Sanskrit meaning happiness.

Another route the Buddha could have taken was overland from Tanjungpura to Santubong. At the onset of the Majapahit Empire, people spread out from Java into the Borneo area.

The people of Tanjungpura came from the Kingdom of Matan. From Matan the people derived from Bakulapura whose name comes from the Sanskrit which means the Tanjung plant. (mimusops elengi)The Tanjung plant is native to Southeast Asia. It forms an edible berry, its wood is used as timber and has medicinal purposes.

From Bakulapura we can trace the name back to the Majapahit Kingdom of Java. As the oral history states, Bakulapura was founded by Brawijaya who had a disgusting skin condition. The people banished him and took sail, landing on the south coast of Borneo. From there he sailed up the Pawan River and stopped at Kuala Kandang Kerbau which is now known as Ketapang.

Legend has he wanted to stay and swam in the river to rid himself of his skin condition. One day, a herd of fish (ikan patin) entered the river and licked his bloody wound until they healed. From that time on, he forbade anyone from eating the fish. From the Bakulapura Kingdom, the Tanjungpura Kingdom was formed.(this story about the ikan patin was published by me in our book “Sarawak River Valley”and attributed to the ruler Indra Siak, 974-1011)

The Indian maritime dispersal began in the later part of B.C. and the beginning of A.D. Trade began supporting the demands of the Roman Empire on the west coast. With expansion of trade came the support of the Buddhist and Jaina monasteries.

The Buddhists became wealthy with trade coming from Java to Ceylon, then to India. From India, the trade continued across India, up the Red Sea to meet with Roman merchants.

The trade between Palembang on the south coast of Sumatra to Java continued throughout the early period. There was also trade between the Palembang and Santubong providing transportation for those who wished to return to China. This second route grew up because of the metal processing which began in the Santubong area. The Southwest monsoon would carry ships from Palembang to Santubong and then to China. The return voyage would travel from China to Santubong and then to Palembang, up the Straits of Malacca, thence over to India.

The one problem is: How ships travelled from Java to Santubong? The only way I can see is that they would have to voyage first from Java/Bali first, then to Palembang, onward to Santubong and then to China.

Faxian, a Buddhist monk who spent ten years in India collecting images and copies of laws, was set to return to China was blown off course and, was said, to have landed in Java. However, if Faxian was travelling to China he would have taken the Santubong route, a much shorter distance than the Java/Bali sail. Therefore, Faxian must have sailed from Palembang to Santubong and thence to China on the Southwest monsoon.

At Santubong we have the development of an Indian port, whereby Buddhist travellers and priests could have established a settlement to attend to the needs of those going to China. The Buddhists had the money and donations to spread the religion.

When leaving Java/Bali, sailors could sail on the Northeast monsoon, with the winds pushing them into Palembang. On the Southwest monsoon, the winds would bypass Santubong on their way to China. Probably, the people did not come from Bali/Java via the sea. The only other way was through Tanjungpura and overland to Santubong.

We have two possible routes the Santubong Buddha could have travelled. The complicated sea route or the overland route from Tanjungpura. The sea route makes the most sense because the Buddha was found near the coast.

References available on request

Bibliography

Ardika, I.W. Ancient Trade Relations between India and Indonesia in Maritime Heritage of India, 1999

Beal, Samuel The Travels of Fah Hian and Sung Yum London: Trubner and Co. 1869

Brown, Robert The Feminization of the Garnath Gupta Buddah Images Bulletin of the Art Institute vol 16, 2002

Coomaraswamy, Ananda The Origin of the Buddha Image in Art Bulletin vol IX,no. 4 1927

Myer, Prudence Bodhisattvas and Buddha:Early Buddha Images in Artibus Asia vol 54,no3/4 1994

Ray, Himanshu Early Maritime Contacts between South and Southeast Asia in Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, March 1989

Rhi,Juhyung From Bodhisattva to Buddha in Artibus Asiae vol. 54,no. 3, 1994

Rhi, Juhyung Reading Coomaraswamy on the Origin of the Buddhist Image in Artibus Asiase vol 70,no. 1

Trepati, Sila Ancient Maritime Trade of the Eastern Indian Littoral in Current Science vol. 100 no. 7 10 April 2001

Verma, Vikus Maritime Trade between Early Historic Tamil Nadu and Southeast Asia New Delhi: Proceedings of the India History Conference vo. 66 2005-2006

Williams, Joanne Sarnath Gupta Steles of Buddhas Life Artibus Asia vol 10 1975