Children of the Missions 1862

Polly

Polly is the eldest and a Kanowit Dyak orphan. She is between 15 and 16 and has lived with us since she was a baby. She was brought to Sarawak by English sailors who were engaged in the Sanskrit and Sakarran pirates in 1849. She is now a good-looking girl with fair skin and light hair. Before Christmas, we hope she will be confirmed and married to the catechist Tom Dayak who teaches the Murdang Dyaks. We hope this young couple will become a missionary couple.

Sarah, Fanny and Phobe

They have been with us for about four years and are orphans of Chinese fathers and Dyak fathers. They were killed or reduced to starving at the time of the Chinese insurrection. Sarah may be around nine and Fanny eight. They used to read English tolerably, understood the history of the New Testament and learned part of their catechism. Sarah has a brother, Simon, who is in the boys’ school. Phobe is a half-cast daughter of Mr. Steele who was killed at Kanowit Fort and a Malay lady. She is a very bright but delicate child about seven years old.

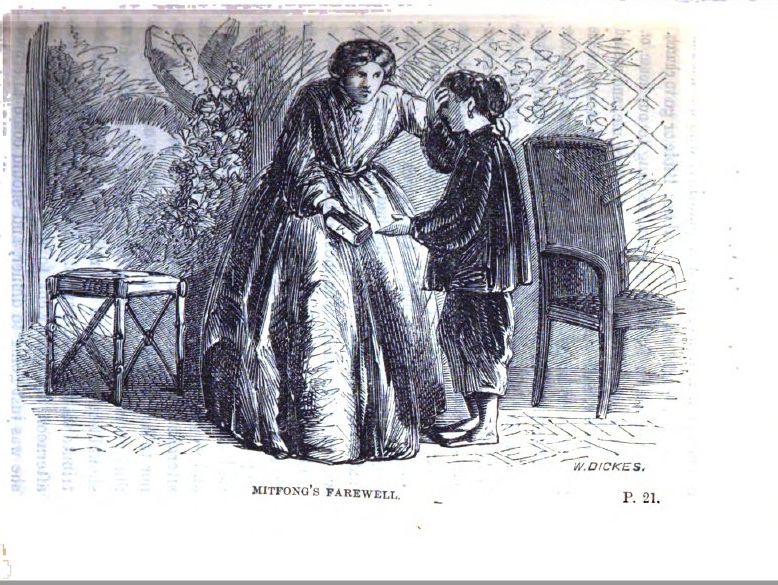

Mitfong

Mitfong is a girl of about 13 years old. She is the daughter of our richest tradesman, baker, general shopkeeper, and builder among other trades. Her mother died soon after birth and begged her husband to give her to me whom she was grateful for some kindness. He promised to do so and she came to live with me when she was old enough. When my eldest daughter, Mab, was old enough to learn, Mitfong shared her teacher and was always so sweet and good child that she was a pleasure to teach. Her father would not leave Mitfong at the mission unless I was there. Mab and I left for England for a two-year excursion and Mitfong was sent to live with her stepmother in her heathen home. She was not allowed to read the Bible or go to church. On my return, Mitfong ran to me and wanted to be close. Her stepmother would not allow her to return to the Mission house but I persuaded her father for her to live at the mission house. Achick (the stepmother) promised that Mitfong was mine.

It is the time of the Ghost Festival, and Achick asks that Mitfong return to visit her mother’s grave. Mitfong said she didn’t want to go because they would keep me. I thought she should go because parental worship is so strong among the Chinese. Mitfong went and my ayah was sent to fetch her back. They said she was sitting down to dinner and they should fetch her back in three hours. Three hours later I sent the ayah back. She had gone to sleep and would come back the next morning. I was getting very angry. The next morning, I was told that Mitfong was going by steamer to Singapore and thence to China. I asked the Bishop to hold Achick in account. The man said he had a letter from her mother in Macao saying they must go and see her before her death. We said all we could to change her mind and even offered him a large sum of money. Achick laughed and said she could get a lot more for her. I asked Mitfong to come to me the next morning and gave her a Bible, and a prayer book and told her to say her prayers. She then departed and I never saw her again.

The Dayak’s

Some months ago, Mr Watson, the English resident at Sarebas sent four children, two boys and two girls. Their parents had been killed by the Sarebas people in a war between them and the Kanowits. The children were the slaves of the Sarebas. The Raja Mudah asked the girls to be taken to Mrs. Koch’s school. They were sent to Sarawak for this purpose but they cried so bitterly about being broken up and the youngest was not to be taken away from the eldest girl that the separation plan had to be given up. The children remained in the fort and slept in a corner of the verandah with three garments among the four.

Meanwhile, the Rajah Mudah was away at Bintulu. The Bishop and I looked at the foursome longingly. Both of the boys had Dyak skin leprosy thought to be catching causing great disfigurement. We were afraid to introduce the boys into the school. I elected to take care of them risking the leprosy.

That very evening, I prepared a meal of tomorrow morning’s rice pudding for the four of them. While they ate, I tried to decide what to do with them. First, I sent Sarah and Fanny to get some of their clothes for the girls and some trousers for the eldest boy. Julia went to the village and bought some mats for them to sleep on. The Rajah Muda sent a present of 10 Straits dollars to help out.

I cleaned out a room upstairs for the children. The sight of other children, a few kind words and suits of clothes had won their hearts and they did not want to go back to the fort. The next day my sewing class made suits for the two boys for it was necessary to cover them from head to foot because of their skin. I also scrubbed them well with soap and water and heads shaved for the boys and close crops for the girls. By evening they looked like different children.

The eldest girl, Limo, who I think is about 10, is bright and clever. She has learned to work very quickly and is now making her jackets. She knows the English alphabet and a Malay hymn.

It is wonderful to see Limo climb a tree. There is a papaya tree outside my bedroom window at least 20 feet high. The tree has a tuft of leaves at the top with the fruit under them. The stem has no branches. To my astonishment, I saw Limo scurry up the tree using her hand and feet like four legs and she plucked the fruit and slipped down to the ground. I told her never to do that again for fear of her tearing her clothes and besides, she did not look very feminine in that position. However, I could not help but laugh.

Ambat, the second girl, is not a sibling to Limo as she was adopted by their mother as is so common among the Dyak families. She is about seven and is such a wild thing! She knows her alphabet and a Dayak hymn but does not speak Malay. In time she will be taught to sew. We have to be very patient with these natives!

I kept the boys in the house with me until the Bishop came. They are now in a room in the schoolhouse under the kind care of Tom Dayak who washes them and their clothes and teaches them. One of our Malay servants says she knows a medicine that will cure leprosy. We have sent it to Singapore for it. I hope the medicine works for the school children to avoid poor Isa and Nigo and they just have each other plus Dayak Tom. I would like Isa to be less grim and be allowed to play with the other children.

I

have one other child as a prospect, a child of one of our Christian carpenters. It is not very easy for us to encourage enrolment in our school. The Malays would not allow on any account their girls to be brought up Christian nor would they permit them to mix with the Chinese. The Chinese have at least a desire for education.

The School

The Rajah Mudah presence for orphaned Dyak children represents our best prospects. No Dayak parent would part with his child. When we have visits from Dyak Christians, they never stay long and they do not result in the children attending the school.

We have collected ten little girls but we do not have the means for adding more. They have a school room next to our dining room which has whitewashed walls and an asphalted floor. Two doors open to the cloister in the front of the house.

In the cloister, the boys of the sewing class sit on mats and work from half past seven to ten o’clock. Julia’s supervisors while I read to them. At 11 they go for breakfast at the school house. At 12 lessons begin. At 3 they sing for half an hour. At 4 dinner. At 5 they have an afternoon service at church. Afterwards, they have a walk with Julia or the ayah. After my ride or walk I return to find the girls sitting under the tree laughing and singing or Polly might be sitting in a wheelbarrow teaching them. At 7 they say their Malay prayers (prayers translated from English to the Malay language?) and go to bed. On holidays I let them play with my draughts set. I wish I had some dolls for them to play with.

The Gospel Missionary February 1863 written October 3, 1862, by Mrs McDougall wife of the Bishop of Labuan

BorneoHistory.net