ABU BAKAR’S REBELLION by Reed L. Wadley Borneo Research Bulletin vol. 38 2007

Along the Embaloh River in Southwestern Kalimantan, Haji Abu Bakar allied with some Iban from the upper Rejang of Sarawak and started a rebellion against the Dutch. What motivated Abu Bakar and his accomplices may have been quite different from the Dutch account. It is difficult to know from the evidence at hand, though Embaloh’s oral history may still preserve the Iban accounts through oral history and other documentary evidence.

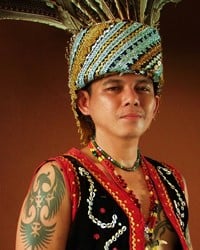

Abu Bakar worked as the Dutch Native representative along the Embaloh River. He came highly recommended by Pangerian Suma, who held the position before Bakar. In a 1903 account, Abu Bakar appears as the son of a Malay noble.

With an Embaloh mother, Abu Bakar was in a good position of local influence and had been responsible for arranging a peace-making ceremony between the Katibas Iban and the people of the Embaloh and Bunut rivers. He and the Katibas Iban were no strangers, their fathers having grown up together.

Some 200 Katibas Iban came to the Embaloh expecting food and favours from Abu Bakar. Although Abu Bakar assured the residents of the Embaloh that they would behave themselves, the people of the river areas were wary.

In early January 1879, Iban raiders from the Katibas attacked a large boat near Nanga Mandai. The five-man crew, along with the traders Sukin (Chinese) and Abang Salim (Malay), fled into the forest. Much of their cargo, including rice, was lost overboard, but about 700 dollars worth of getah (forest latex) was stolen. The raiders carried the stolen goods to Bukung and Belimbis before moving on to Sarawak.

Dutch officials determined that the raiders were led by Sanang (a.k.a. Keling), son of the headman Unggat, who was allied with Abu Bakar. At about the same time, Abu Bakar had swindled an Arab trader named Sheik Imal at Nanga Embaloh – selling him 10,000 gantangs of rice for 400 dollars but only delivering 2,000 gantangs. A few days after the Iban raid, Abu Bakar left for Sarawak (with five small cannons he took from the government outpost at Nanga Embaloh), claiming his mother was ill.

During his investigation in mid-January, Controleur J.C.E. Tromp became certain that Abu Bakar had planned an attack with the Katibas Iban most likely against Bunut and five Embaloh settlements, using the stolen money and goods from the raid on the boats to finance the assault.

He gave people in four of the most upriver Embaloh communities – Keram, Bukung, Belimbis, and Pinjawan – the choice of following him or having their houses burned. Abu Bakar held influence in those communities, especially Belimbis and Pinjawan where his mother and other close relatives lived.

Not only was the attack and robbery near Nanga Mandai led by Sanang but several Embaloh were involved as well. The raiders carried the stolen goods to Bukung and Belimbis before moving on to Sarawak. Following Abu Bakar, people from those four communities also transported their household wares to Sarawak, while hiding other valuables in the forest.

A Palin headman, Benuang, left for Sarawak at the same time with some 60 households, after giving Sanang several ceramic jars and other valuables, and Abu Bakar supposedly threatened others who did not want to move to be beheaded by the Iban and having their headless corpses thrown into the river to give notice to the Malays of Bunut and the controller. In addition, Sanang and his men had extorted chickens, taro, and other food from the inhabitants of Ulak Pauh, Paat, and Nanga Sungai when they had passed that way to Sarawak.

Although they were convinced that the Embaloh themselves would not join Abu Bakar’s attack, as a precaution, the Dutch stationed an armed boat at Nanga Embaloh. People in the remaining Embaloh settlements also prepared for the threatened attack from Sarawak. The attack, of course, never came.

Notified by the Dutch of Abu Bakar’s and Sanang’s activities, the Sarawak government arrested them in March or April, and the two men quietly faded from the documents. How long they stayed in jail and how much of the stolen goods were recovered may be hidden in the Sarawak archives. Presumably, the Embaloh who were conscripted by Abu Bakar returned home and resumed their old lives.

However, in a postscript to his report, Resident Kater mentions that the Assistant Resident received a letter from Abu Bakar (presumably before he fled to Sarawak?) saying that the Malay rulers along the Kapuas were in league against him. This provides the only hint of motivation, suggesting that, instead of a rebellion against the Dutch per se, it was local-level political disputes that motivated Abu Bakar’s efforts.