Tom’s note: This account about the infrastructure of Sarawak is probably one of the most unintentionally hilarious histories of the times of the Second Rajah Brooke.

Coal

Outcrops of coal existed at Silantek and along the Sadong river. Mr St John was dispatched to explore the coal findings. However, he suffered from malaria and also ran afoul of the Dayaks. The local people claimed that some fearful calamity would befall them if the coal fields were disturbed. St John reported the coal was indeed found in abundance. Many things happened at once. Samples of coal were sent to Singapore, and the ore was found to be of good quality. The Rajah was elated, and he endeavoured to float a limit liability company with 1500 shares at $100 each, with the Rajah as Chairman of the Board. However, there were no buyers. The Rajah then opened up the Sadong deposits and mined enough coal to supply the government’s coastal vessels.

In 1877 a contract was let with a local Chinese contractor to excavate 250 tons of coal who utilized the coal for a run from Singapore to Hong Kong. The test was successful, but no one came to work the coalfield.

The Island of Muara, just inside Brunei Bay, was home to the C.C.Cowie and Sons, who excavated coal for the Sultan Brunei. In 1888 the Sarawak Government purchased the island and renamed it Island Brookston. The concession was placed in the name of the Rajah. Two years later, a disastrous fire broke out, which burned for two-three years, during which time nothing could be done to extract the coal.

The Rajah then wanted to work the Silantek coal fields. In 1896. He commissioned a study and found that a rail line between Silantek and Lingga would cost $100,000 in 1896 dollars. The idea was abandoned.

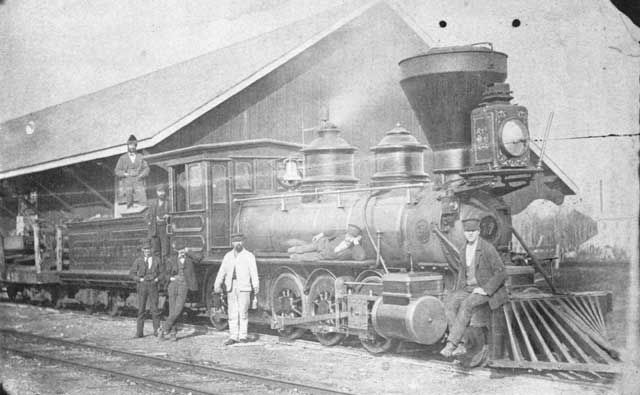

Most of Sadongs production was used locally, while Brooketon provided bunker coal in opposition to the Labuan coal field. The Sarawak government owned two colliers, the brigantine “Black Diamond” and the SS Vyner. The Vyner was found to be too small and was replaced by the charter vessel, the Norwegian SS. Breid. Coastal transfers were made by the S.S. Lorna Doone, which also towed a barge. At Sadong, the coal was transferred from the pit head to the wharf by rail. Two locomotives were employed -the Sampson and the Sadong. One of these blew up and was replaced by the Skipalong. Brookston was closed in 1924, and Sadong, at the time of the great depression, closed in the early 30s.

Mercury and Gold

The Borneo Company, under the head of Mr Helms, did much to open the mineral potential of the company. For forty years, they mined antimony at Busau and mercury from Tegora, both in the Bau district. In the 1880’s they assisted the Chinese gold miners by providing basic mining machinery. In 1898, with the advent of the cyanide extraction process, the company opened the Tai Parit mine in Bau, followed by open cast workings at Bidi in 1900. In those days, these ventures were described as the greatest workings in the world. It isn’t easy to visualize that Bau was the centre of a major industry with hundreds of people. Bidi mine closed in 1911 and Bau in 1923. Interestingly, these two mines produced over half a million ounces of gold worth some two and half million pounds. (1960 pounds)

Rubber Estates and Timber

The company started Dahan and Sungei Tengah rubber estates and great plantations for planting gambir (used in the dyeing industry) and pepper.

A certain amount of timber extraction was undertaken along the Rajang river, but this was never a complete success due to trepidations of the borer beetle. Most outputs went from Tanjong Mani to Hong Kong.

Steam Boat Travel

The Borneo Company formed the Sarawak-Singapore steamship Company. The new company took over the old steamship Royalist II. Friction was soon created, and in the same year, the government disposed of all its shares. They were taken up by the Borneo Company and leading merchants in Kuching and Singapore. The company purchased the Rajah Brooke and, in 1890, offered fortnightly services from Kuching to Singapore. In 1896 the Rajah Brooke ran aground at Pulau Tinggi and became a total loss. A fearful outcry resulted in the total disruption of trade. The company was accused, amongst other things, of carrying out a monopoly of trade and transit. The Rajah Brooke was then replaced by a chartered German vessel, the Vorwarts, but she also ran aground the following year.

In 1902, a Chinese Company placed service in competition, which lasted only a year. They then convinced the Sarawak-Singapore Steamship company that two small vessels could replace the large ones. They ordered a further ship, the S.S. Kuching.

Except for Kuching town, there were no roads, and travel had to be on foot or water. The Rajahs steam yacht Aline and the first Zahora provided transportation up and down the coast mainly for government servants.

Railroads

For many years the Rajah wanted a rail line. Although studies were completed for a 27-mile line, the line only went to the 10th mile. The story goes that when the Rajah returned to England on leave in 1907, he solicited help from the old Great Western Railway directors. The Chief engineer suggested more reliable advice might come from Gamages, a hardware store in London.

Track laying commenced in 1911 with the assistance of the light locomotive “Idiot“, and in 1912, orders were placed from Picketts of Bristol for one 0-4-0 tank engine, the Jean and two ten-ton 4-4-0 tank engines, the Bintang and the Bulan. Second-hand rolling stock was purchased from the Burma railways and further stock from the Federated Malay States Railways. The whole lot was picked up S.&S.S. Co Steamer Natuna on a special round-trip voyage. The railway opened progressively to travel in 1915, with the official opening taking place on 1 August. On opening day, the first train knocked down and killed a child at the Green road level crossing, and this was considered to be a very bad omen.

The system was well served with stops at Kuching Central, Green Road, Batu Tiga, Batu Lima, Batu Tujoh and Batu Supuloh. These stations were all connected by telephone lines. Fares were very modest, with costs of 3 cents between stations and 20 cents for the whole ride.

The building of a road next to the railway killed the business. A host of ramshackle buses appeared and undercut the railroad’s modest fares. In January 1931, the Rajah ordered the railway to close after losing $1,063,760. The railway was used for hauling stones until 1947.

The Japanese reintroduced limited passenger service, and prisoners of war employed at the 7th-mile quarries have painful memories of the operations there. The little left of the railroad was disposed of as scrap to Singapore in 1959.

The Brooke Dockyard

The Brooke Dockyard was planned in 1907 at about the same time as the railway. Excavations commenced in 1909 when the contractor absconded with the funds in 1909 and construction halted. Work was finally completed in 1912, and the dock was declared open by the Ranee Mudah in September of that year.

The Ranee Sylvia gave an account of that function in her autobiography “Silvia of Sarawak”.

“We had not been in Sarawak long when I was asked to perform the ceremony of opening the new dry dock. I shall never forget the ceremony as long as I live. It was announced in pamphlets and in the Sarawak Gazette as one of the most important events in the history of Sarawak Public Works. Vyner(the Rajah) was nervous; any public ceremony has always struck him, and his restless timidity infected me so that I was already in a bath of perspiration before I was dressed. We all three sallied forth at 5 p.m. and proceeded boat upriver until we arrived at the entrance to the dock. A bugle call from the boat heralded our arrival, and the gate of the dock was flung open. We were then paddled to the steps inside the gate, up which we ascended to the dias and prepared for our reception. After being presented with an enormous bouquet of wild orchids smothered in ants, I was invited to declare the new dock open. I can remember so well stepping forward and saying in a voice that sounded like a hinge that needed oiling. “I declare this dock now open and name it Vyner Brooke’.”

The commotion that ensued was incredible. Vyner had prepared a magnificent speech which he endeavoured to deliver. But, in the meantime, the Chinese and Malays had gone crazy with exciting activity. They plunged into the water with ropes between their teeth and swarmed upon the platform laughing and screaming to one another instructions and wishes of good wilL. Vyner’s speech was spoken but unheard. We dare not look at one another, and we were on the borders of hysterics”.

Water

Until 1907, Kuching was dependent on the small reservoir in Reservoir road for its water supplies. This proved inadequate for its water supplies, and in 1903, a plan was developed to bring water from Matang. This allowed for a 4 million gallon water reservoir and a piped supply in the town, a distance of ten miles. The pipes arrived in 1906 and were ready for the grand opening in August 1907. This was postponed and finally cancelled when the pipe burst. “It took time to get over the teething troubles.”

The street light was introduced in 1906. The lamps were of the incandescent gas type. The iron poles were reported as giving the lights a smart look.

The telephone system was installed in 1908 and extended to Bau and Bidi. Wireless stations were erected in Singapore, Simunjan, Miri and Sibu. The first message to Singapore was relayed on 25 October 1916.

Private concerns included a kutch factory built in the late 1890s and closed in 1959. The old steam engine and its huge flywheel were a sight to see. A jelutong factory was established in Goebilt but was subject to liquidation a few years later. Tea and coffee were grown on the slopes of Matang, and tobacco at Lundu. Sarawak cigars were on sale in London with a picture of the Main Bazaar on the box.

From: Economic Development under the Second Rajah 1870-1917 Sarawak Museum Journal 1961 A.H. Moy-Thomas