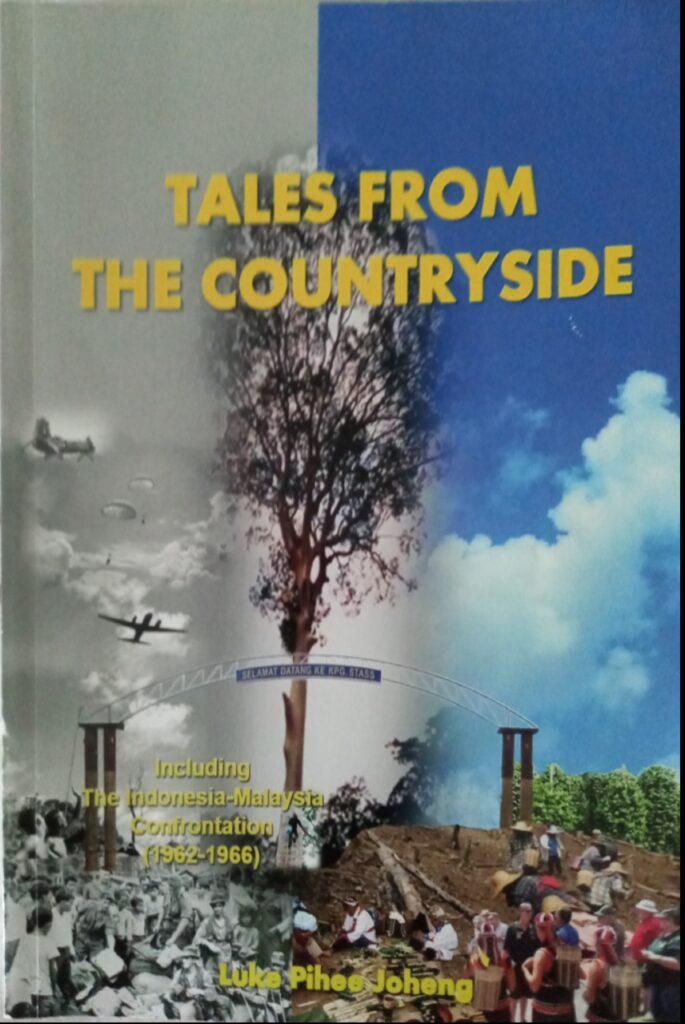

Tales from the Countryside by Luke Pihee Joheng

Review by Tom McLaughlin Borneohistory.net

A Bidayuh Journey

Tales from the Countryside is a beautiful book about the origins and coming of age of a Bidayuh resident in Kampung Stass and the history of the Malaysian Indonesian Confrontation.

Chapter one tells of the oral history of the origins of the Bidayuh. Although a bit fantastical, these origin stories inform the migration from the mountain top of Sikung West Kalimatan into Sarawak. They seem to date from 583 A.D. and include the eruption of Mt. Krakatoa in 1883. Very little is mentioned about the splits into Bidayuh Serian, Bidayuh Bau, Bidayuh Pawan and other groups and how the different languages arose. However, this is oral history, and unless one immerses oneself in the people’s culture and profound language, one cannot expect answers to these deep-seated questions.

Like cartoonist Latt expresses his world in drawings, Joheng tells about his world in words. Phrases like “we were happy and contented with the world around us” and “above the sky was blue as the depths of an ocean, with great white clouds slowly glided by like giant ships” helps to expand the readers’ imagination and paints a picture of the place where he grew up.

Vivid descriptions of the houses, living in the homes, music, pigs, fowls, dogs, cats, insects and demons are described in excellent detail paragraph by paragraph. The planting of the fields, omen birds and the naming of the people are written to not forget the visions implanted in the brain.

The arrival of the fruit season, especially the durian, is heralded by the Kangkuk bird. A shy and elusive creature, only its call is usually heard. Local cultures all have this portent to the durian but this description plants one into the centre of kampung awaiting, hungrily, the drop of the first fruit. Excitement builds from flowers to the mature orb that crashes through the forest, landing with a loud thud on the ground and people scattering to retrieve this wonderful spike-covered gem.

Mangosteen, langsat and other fruits play second fiddle to the great durian. Sadly, such customs came to an end as the trees were old, customs waned, and modernity took hold. However, those who lived through the season will have a memory that will last a lifetime.

The next chapter is about honeycombs. The old days of collecting honey and the excitement it generated is alive and well in this book. The clearing of an area around the tree, the building of a small hut, the construction of a sixty-foot ladder, and the lighting of the fire is all expressed on these pages. The singing of ancient songs caused me to hum along with any of the old Elizabethan chants that I recalled. I am sure the Bidayuh could chortle much better than I did. Finally, the combs are split into sections and divided among the kampong.

Chapter Five tells of the communal bath place. The river was the central playground of the boys who jumped, splashed, played games and attempted boating. The collaborative bath place was the purview of the adults who traded gossip, washed clothes and courted. The bathing platform was made of big timbers that could hold ten people. After the washing, women often jumped into the river, and the sarong would form a large bubble and allow the women to float around. The fears of rainbows, summer showers and tales of idiots who plied the river are told. The memories of the river and the bath place are wonderfully recounted in this chapter.

The great ‘Pinyamun’ scare reflects the history of the Bidayuh. As the Skrang (Iban)head hunters moved north, the Bidayuh were the centre of their carnage. The Bidayuh were also looked upon by other tribes, especially the followers of Makhota of Brunei, as a civilization whose people were beneath them and were taken as slaves. It wasn’t until James Brooke arrived and stopped the headhunting and prejudice. However, fears still lingered.

People were told that head hunters were coming, and they refused to work in the rice fields. The lights and radios were kept low at night, with guns and knives kept close to the men. Rumours were readily believed, often spread by the women at the bathing place. The children were told that the head hunters would come if they did not behave. The Pinyamun became apparitions to move from one place and, seconds later, to another. Many believed in these ghosts, but a few did not go about their lives as normal but with a wary eye on what was behind the next tree.

Tuba fishing was part of Kampong life. The tuba were from a plant whose sedation on the fish was mild and short-lived. The fishing came at the beginning of the dry season, where water and fish would be scarce for the next three months. The tuba plants were added to the water, and the fish became stunned, caught and dried to last through the dry season. The waters would return during the rainy season, and so did the fish. Many fun and riotous antidotes are communicated to the readers during this period.

One of the more bizarre stories in the book tells why the pigs have brown stripes. It seems the sow had a litter but had to visit the rice field to eat. Her departure left the piglets alone. Along came a mouse deer dressed in a top hat with a cane. He teased the piglets and said they were dirty and smelly. The piglets cried when their mother returned, telling her of the antics of the mouse deer. This went on for about three times when the sow decided to stay home and confront the mouse deer. The sow encountered the mouse deer, and a wild chase ensued until the sow got stuck in a hollow log. The mouse deer had his way with her and from then on, the piglets had brown stripes.

Kuu-LiIh-HIIh has two meaning in Bidayuh. The first is to encourage the flames in the burning of the rice fields to flame up and burn faster, while the second meaning refers to a super sexy woman wearing red. Both are hot, red hot. Through the eyes of the kampong boys, we see how the rice is planted and harvested. What we may think as a tedious job is made fun of and delightful through those eyes. Omen birds, ants carrying a piece of food, and other superstitions were part of the planting process. The courtship was demonstrated by exposing oneself to the intended. It is all part of the fun and games of planting and harvesting. Catching and eating grasshoppers, the making of toddy and how the sago palms produced starch are all told in a marvellously adventuresome way.

Chapter ten is called Three Dyak Nights.

This chapter is chock full of details about the Gawai celebrations. From the ancient traditions to the bands and songs that were played during the second night to the peddlers and the hectic packed gawai house, the passages are wrapped in detail, too much to be related here. Mr Joheng lets the light shine through his words, and one feels the intensity of the dramas and rituals played out. The passage is written with passion and emotion that one wishes would never end.

Chapter 11 is the story of the Malay-Indonesian Confrontation. Little is known in the Western world about this passage from 1962-1966. I had heard of it, barely, but had not become aware of its effect on the people.

The chapter begins with an explanation of the Cobbold Agreement and continues on with the Malaysia Agreement of 1963, MA 63, and details how the federal government eroded the powers of Sarawak. Next comes the Petroleum Act of 1974, followed by the Territorial Sea Act of 2012. All four of these legal documents are explained in plain English so that everyone can understand them.

A fascinating biography and the political workings of Sukarno on how he was able to sway the Indonesian people to back him is related. A powerful orator, his lavish and licentious lifestyle, and his command of the armed forces all led to the image of a great ruler to the people.

The first incident was the Brunei Rebellion. In 1962, a force under Sheikh Azahari, the self-proclaimed leader of the Sarawak, Sabah and Brunei, attacked the Shell oil depot at Seria. This included a power station, police station and government facilities. The British military intervened, and it was proved that the guns and training had come from Indonesia.

The remaining rebels, under the command of Salleh bin Sambas, fled and attacked Limbang, which they held for a week. The Royal Marines from Great Britain managed to dislodge the interlopers.

The Stass regulars became known as the Rampaging Boars. The remnants of the group that had seized Limbang were their targets, and they chased them back to Indonesia. They formed an irregular group chasing after the Indonesians and received a bounty for the fingers, ears and scalps removed from the enemy. They disbanded after the British takeover.

I never knew there were so many battles. The Battle of Staas, The Battle of Blubai-Kindau, the Battle of Babang, the Battle of Kg. Kumba, Camp Bukit Knuckle, to name a few. The real confrontation cost 4,345 Malaysian lives, with 519 commonwealth casualties. These conflicts are outlined in detail in the book. The sad fact is that the children of today and yesterday will never know about the brave men who fought so bravely for them.

Tales from the Countryside can be purchased from the author. Call 0128870112