The Chinese Revolt by Rev. Brian Taylor SMJ 1969

The first woman, other than women with their husbands, ever sent abroad by the Society for the Propagation of the Bible was Sarah Coomes.

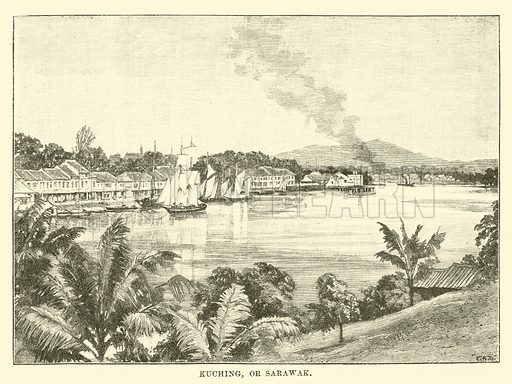

Miss Coomes was left behind in the first evacuation of the town after the Bau Chinese had arrived to pillage and sack Kuching. Before, she taught girls from the book of learning “Sing Song”. (Sing Song, a corruption of Sin Sang, a teacher, was the nickname of Foo Nguyen Khoon, a Chinese catechist. He smuggled his wife out of China at a time when women were not allowed to leave and went first to Singapore and then to Pontianak, where he practised as a teacher. He fled Dutch Borneo because of the fighting and came to Sarawak with his family as refugees. He was employed by the Anglican Mission as an interpreter in 1851 and baptized in 1852. On 11 January, he was ordained a deacon by Bishop McDougall, perhaps the first Chinese anywhere to be admitted to the Anglican order. He returned to China in1881.)

When they learned the boat was to return to Kuching after the revolt .”My life aboard the steamer was not an ideal one. I had many little services to perform for Miss Wooley and the Rajah. The Rajah especially did me the honour to employ me to make baju (clothes) out of my old dress, washing a small stock of clothes and dressing his leg, which he had injured during his flight.

As soon as it was considered safe to go ashore, an armed crew accompanied me to the Mission House. I was the fully employed trying to save the remnants of the Bishops’ property and

brought large parcels of clothing to the ship. I found beneath a heap of broken glass the Bishops’ private papers and sermons. I also saved a good many garments of my own. It seems the rebels did not desire already made clothes. Pieces of cloth were more attractive to them. I was very thankful for the dresses, as I was to supply Mrs Middleton and the doctor’s wife, who had lost all by fire, with a change of clothes.

A few more words about the Dayaks. Going ashore alone one day, a curiosity prompted me to go to the end of the main road, which is two miles long with clearings and gardens nearly all the way. Once enlivened with many Chinese dwellings, now nothing but heaps of black ruins.

I had gone to the end of the road when suddenly a large party of Dayaks emerged from the jungle path armed to the teeth. They stared at me with the utmost astonishment. At length, instead of molesting me in any way, they asked for my permission to go on.

On another occasion, being alone in the mission house, after wandering from room to room without hearing or seeing servants, the livestock being dead or driven away. I was about to return when five Dyaks armed with parangs made their appearance from the Bishop’s bedroom. I asked them what they wanted when they said they were “just looking about.” It did not appear they had taken anything as they had no baskets or any means of concealment. Indeed, although the houses remained open day and night, it does not appear that anything was ever stolen by the Dayaks. They take nothing but the fruits of the earth, which they consider common property.

When peace was restored, I resumed my employment with three mission families. One of them, a Chinese girl was sent to Singapore. Sing Songs children were there with three other Chinese. These last three were soon banished with their entire family because the father was a suspected person.

During the disturbances at Sarawak, I had many opportunities of observing the various tribes of Dayaks who came to Sir James’ assistance. The Serebus and Sakarran are very stout and a well-built race of men with a ferocious appearance. To me, however, they were uniformly kind and gentle. When walking in the town, when I met a party of them, they would form a line and let me pass, expressing much wonderment at my appearance. One of them detached one of many rings from his ear and offered it to me, which I accepted. When several of them came to visit me, I gave them beads, pieces of print and cloth. Sometimes Owen would send away 2 or 3 natives in full English costumes. This was, of course, before the war. Afterwards, we had little to bestow. It was very amusing to observe the wonderment of it all. The greatest English marvel to them was the steamer.

On 9 April, she left Sarawak Town to go to Lundu to assist the Reverend W.H. Gomes. For a while, she was happy there, but she found there was not enough to keep her occupied, and she was too old to adapt herself to village life. After a few months, she returned to Sarawak Town, went to Singapore, and took a teaching appointment. Miss Comes would also return to Singapore to teach.

Tom’s Notes

It is interesting how she thought it was an honour to wash the Rajah’s clothes. She kept referring to Kuching as Sarawak Town, which means the name had not yet been changed to Kuching. It seems the Dayaks were very rare in the town area.

From:

Taylor, Brian Rev The Chinese Revolt in The Sarawak Museum Journal 1969