The Discovery of Brunei Oil

A Borneohistory.net Production

In 1906, Brunei was ruled by the British under the residency system. In dire need of some form of income, oil was considered an answer to the problem.

Any company that wished to explore for oil had to obtain a prospecting license from the British Resident. In 1906, six licenses were issued. These six unnamed companies had difficulty with the wet weather and the transport of drilling machinery into the jungle.

In January 1907, Carl Gadelius, a merchant from Singapore, obtained a prospecting licence. Under his name, a company, Shanghai Langat, from the Netherlands, was formed. The concern performed half-hearted explorations in Jerudong and Tutong districts. Their efforts were unsuccessful. They withdrew from an agreement in 1917.

Meanwhile, a company with the Royal Dutch Group, The Anglo Saxon Petroleum Company in Sarawak, had been successful in Miri. The Company had asked for concessions in Brunei but were denied by the Brunei (British) government. In 1911, the Company wanted to build a pipeline across Brunei to a proposed oil refinery at Brooketon (Muara).

Rajah Charles Brooke supported the venture. The Brunei British government agreed to the oil refinery but not to the pipeline. Possibly, the British Resident felt the demand by Shell Oil were excessive. The Anglo-Saxon oil company tried again in 1914 but was denied. They also applied for prospecting licences in 1911, but they were also denied. Finally, in 1913 the prospecting licences were granted for the province of Tutong. Explorations proceeded haphazardly mainly because of WW 1 and their need to concentrate on the Miri Oil Fields.

The British Borneo and Burma Syndicate applied for a prospecting license in 1911 for explorations in Belait. The licenses were granted, and they vigorously explored oil in 1912, but they did not make a significant strike and ran out of money. The British Borneo Company and Anglo Saxon Company entered into talks searching for cash.

During this period, the Sarawak Rajah, under the name of the youngest son, lay claim to Brunei oil under questionable circumstances involving the acts of 1883 and 1890. This dispute lasted until 1914, when the Sarawak Rajah finally agreed the claims were spurious.

An unfavourable report by a geologist coupled with the delaying tactics of Rajah Brooke caused the Anglo Saxon Oil Company to break off talks with the British Borneo company. During these negotiations, they had formed the Brunei Petroleum Company. Now, they had the Brunei Petroleum Company, which had no money.

The British Borneo company tried to find funding. They looked for financing from Standard Oil, D’Arcy company ( rejected because of geology reports), the Kuhara company of Japan(talks failed) and finally back with the Anglo Saxon concern in 1922. The British Borneo Company and the Anglo Saxon Company formed the British Malayan Oil Company with 100,000 pounds. Vigorous explorations followed with oil being discovered in exportable quantities in 1929.

Under the reign of Sultan Hashim(1885-1906), the Sultan had decided to sell oil leases to individuals at a fraction of their value. They, in turn, would sell them later at a significant profit. The British then “persuaded” the Sultan not to sell them at such a meagre cost. The Sultan then stated this was the end to Brunei independence. Coupled with this, the Rajah of Sarawak’s coal mine on Berembang Island had struck oil with the strike of a pick. The Rajah of Sarawak was irritated by the strike because it inferred with coal mining. The two incidents caused London to approve a Resident in Brunei in 1906.

The Resident was to encourage bona fide mining companies to purchase prospecting leases and invest in Brunei. This would provide funds for the British administration and for the people.

The British Mining Act of 1908 had several parts. The first was that the British had the right to revoke the license if they found the oil company had violated the agreement. The law would include prospecting in an area not designed or continuing to prospect after the lease had expired.

The second part was the British Character Clause. The clause stated that most holders of a company who began drilling for profit must be British citizens and that the Company must be registered in British territory. Provisions were also made the oil was to be sold to benefit the Royal Navy.

There were exceptions. Brunei oil was refined in Sarawak, not a British territory. Compromises were also made with the D’Arcy company when their leases expired. Subleases of Mr Gadelius, a Batavia concern, were allowed. Finally, when people complained that Shell Oil Company did not meet the requirements of being British owned nor British directed, the response was “Brunei was not quite like other places: Its main need was capital and for my part I didn’t mind where the capital came from as long as it came.”

During the latter part of the nineteen-teens, the British Government-backed British Brunei Petroleum hoping the Company would find a British backer. It was okay if the Japanese Company, Shell and others prospected for oil, but quite another matter if they wanted to export oil. To sum up, the imperial policy was to encourage genuine mining operations in Brunei, BUT the resulting oil field was to be kept in the control of the British Company.

The problem was resolved in 1922 when Shell Oil company formed a subsidiary British Malaya Oil company with British backers. Shell agreed further to pay British Brunei Petroleum one schilling for every ton of oil produced.

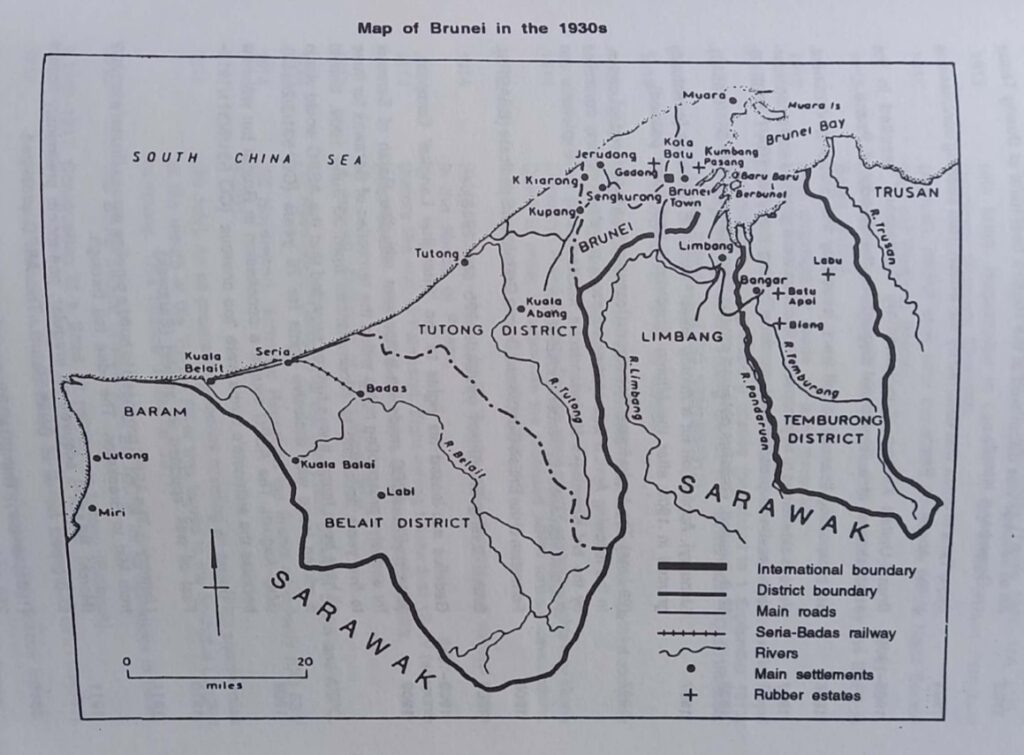

Under the name of British Malaya Oil, Shell Oil company invested heavily in Brunei. Roads were built, wharves constructed, bungalows erected, a railway was tracked, and offices were set up. It became apparent that Shell Oil knew something that London did not. All the work was being performed in Belait province but not in Tutong.

In April 1929, oil was struck at about ten miles north of Kuala Belait, close to the Seria River. With the infrastructure already in place and a pipeline run from Seria to Lutong Sarawak, the oil fields were ready for production. The oil field produced a small amount of oil but turned into a gusher. Uniquely, it was the type of oil that was required for aeroplanes. By 1935, Brunei oil became the commonwealths third major producer after Trinidad and Burma.

It is not known whether the British or Shell Oil company paid anything to the Brunei people in the early days of the exploration. What is known is the people of Brunei were never consulted.

From: AVM Horton “A Pauper with Valuable Oil For Sale” The British Borneo Oil Syndicate and the Search for Oil in Brunei 1906-1923 in the Sarawak Museum Journal December 1995