Raffles and West Borneo

The first Chinese miners were probably brought from Brunei between 1740 and 1745 to Sambas. The Malays rigidly controlled them until 1760, when they were able to throw off the Malay yoke and establish their own Kongsi.

The Dutch discouraged immigration from China until 1791 when Dutch forces were withdrawn from the area. By 1812, the population may have reached 30,000, most of whom were Hakka, Hokiens, and Cantonese.

In an effort to find out what happened to the HMS Commerce and other sailing vessels, Stanford Raffles, then Governor General of the Malay States, sent a Mr F Burn to Pontianak to act as his political and commercial agent.

On arrival, Burn discovered that the Raja of Sarawak had indeed captured the Commerce, had plundered and burnt her, and had sent the Captain and forty-five of her crew as slaves to Brunei. The cargo had been sold, and the second mate put to death “in a private manner”. Before burning the ship, the Raja had written to the Sultan of Pontianak offering her for sale, but this had been refused. Burn told Raffles that he himself had seen the correspondence.

The fate of the Commerce and the loss, shortly afterwards, of the brig Malacca (from which the Sultan of Sambas stole a cargo of tin valued at $ 14,(00) give some indication of the seriousness of the pirate menace on the West Coast of Borneo at this time. The number of ships lost through various forms of piratical outrage had been growing steadily for some years and, paradoxically enough, this increase was due to British dominance at sea.

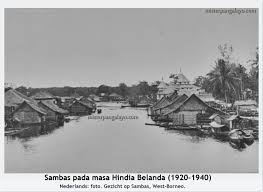

Most observers agreed the headquarters of the pirates was at Sambas. The decay of the Sultanate of Soekadana left only two rivals in the area: Sambas and Pontianak. Sambas was pirate-infested so most trade was diverted to Pontianak. The result was that by 1812 more goods were being imported through Pontianak for the Sambas Chinese than were coming in through Sambas itself, and Pontianak prospered as the trade of Sambas fell away. Raffles would offer a degree of protection to Pontianak while trying to suppress trade with Sambas.

Accordingly, a naval expedition under the command of Captain J. Bowen, R.N., sailed against Sambas in October 1812. Bowen’s orders were to destroy the town and port completely, for Raffles wanted an example made of Sambas so that other pirates in the Archipelago might learn from its fate.

However, when Bowen entered the river to Sambas, the attackers came under a barrage of fire from the shore batteries and from the guns of a squad of Lanun pirates who happened to be anchored there. Bowen was compelled to make a withdrawal, a major British defeat.

Raffles then proposed a treaty with the Sultan of Pontianak. He sent John Hunt as his commercial agent. Raffles did not want to make a colony of Pontianak only to secure trading rights. However, trading could not be secured while Sambas remained in control by the pirates.

A well-planned and armed British expedition under the command of Colonel Watson attacked the Sambas fortifications from the rear. After a half-hour battle and the loss of 150 defenders and only eight British soldiers, a letter was sent to the Sultan demanding the surrender of the pirate chief Pengeran Anon. There was no reply and Pengeran Anon escaped into the interior.

Raffles then organized a blockade of all Borneo ports except for Banjarmasin, Pontianak and Brunei. He sent Captain Robert C. Garnham to visit various harbours in Borneo “The intentions of Government”, Raffles told Garnham, “are decidedly not to leave eventually a Single Pirate on foot in the Eastern Seas”.

On his arrival at Sambas on September 10, 1813, he told the Sultan he would restore him to the throne if he would accept a British advisor. He admonished the Sultan of Sarawak about piracy by letter and went on the Brunei to talk to the Sultan. On October 24th, aboard H.M.S. Malacca in Sambas Roads, His Highness was restored to his ancestral rights and a treaty of perpetual peace was signed by the Government of Java.

Captain Garnham’s diplomatie successes on the West Coast represent the high-water mark of Raffles’ Bornean policy. In eighteen months the Lieutenant-Governor had founded a settlement at Bandjermasin, begun the work of suppressing piracy, arranged for the appointment of British residents at Pontianak and Sambas, and brought the Sultan of Brunei into the British fold. The four largest native states on the island either recognized British sovereignty or looked to the British Government for protection.

Raffles was able to accomplish all of this because of his relationship with Lord Minto the Governor General of India and his boss. He knew Lord Minto would cover for him. However, Lord Minto was replaced on October 4th, 1813, by a new Governor-General, Lord Moira.

Lord Moira ordered Raffles to halt all actions towards Borneo until “he could catch his breath”. Raffles sent him a long missive explaining his reasons for his actions. Lord Moira replied, among other things, that he did not believe that the princes of Borneo were really anxious for British protection and, in any case, the process of ‘civilizing’ them would cast a great deal of blood and money. He was prepared to give grudging approval to the continuance of the Bandermasin settlement but insisted that all other plans, like the blockade, for Borneo be discontinued immediately.

At the close of the war in Europe, the British government debated which colonial possessions should be returned to the Netherlands. The sugar lobby in the House of Commons was in favour of retaining Demarara, Essequibo, and Berbice, all on the north coast of South America. The Navy wanted Ceylon and the Cape of Good Hope. This left the Dutch East Indies to return to Holland.

On August 13, 1814, an agreement was signed in London. This agreement laid down that “the Colonies Factories and Establishments which were possessed by Holland at the commencement of the late War, viz. on the 1st of January, 1803, in the seas and on the Continents of America, Africa and Asia, with the exception of the Cape of Good Hope and the settlements of Demarara, Essequibo and Berbice” would be restored to Dutch sovereignty. Britain ceded the island of Banka in exchange for the Dutch possessions on the Malabar Coast of India, and suitable arrangements were made for safeguarding the property of merchants and landowners likely to be affected by the change. No mention was made of Banjarmasin. Stanford Raffles was relieved of his assignments as Governor General of Java in 1815.

From: Irwin, Graham Nineteenth Century Borneo: A Study in Diplomatic Rivalry ‘ S.GRAVENHAGE – MARTINUS NIJHOFF, 1955

BorneoHistory.net