Kutai

I have always wondered about Kutai and its history. I had visited there but never really intellectually explore it. Here are two condensed articles on the kingdom for your enjoyment.

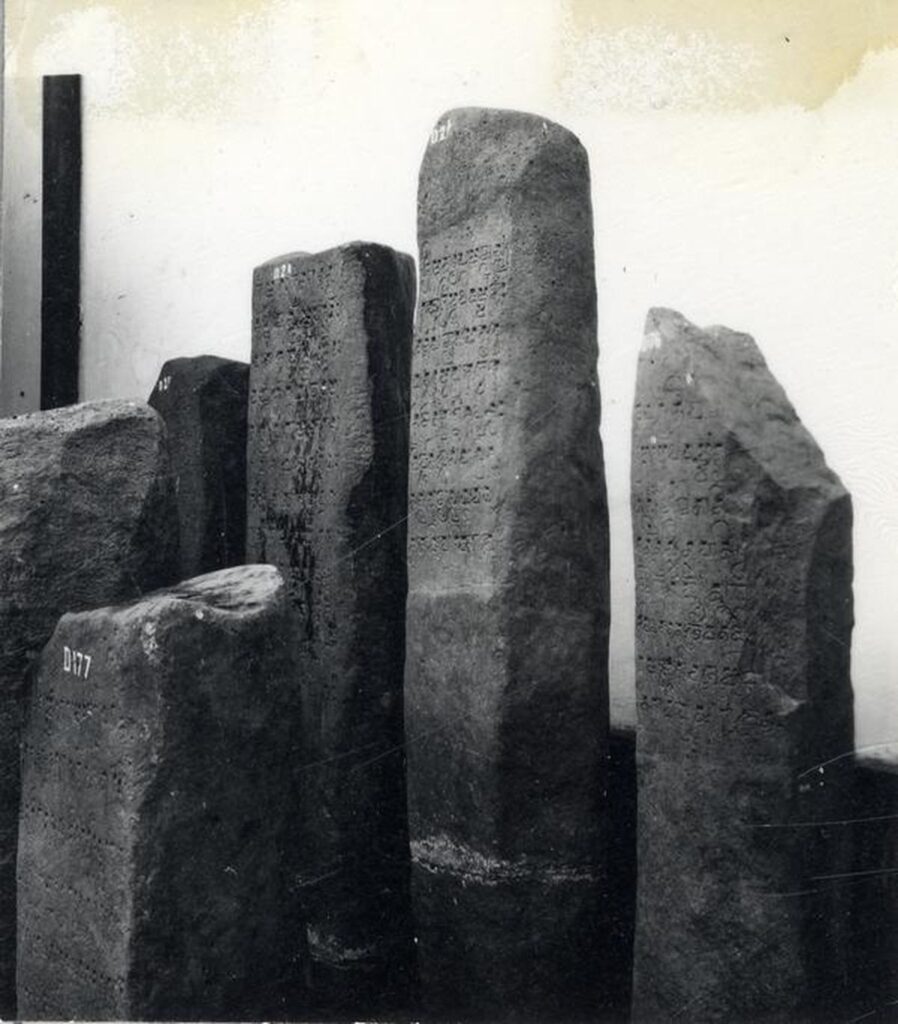

The oldest known inscriptions in the Archipelago were found in Kutailaman Kutai. These consist of four stone sacrificial poles (Sanskrit: yupa) dating from about 400 A.D., on which in Pallawascript metrical Sanskrit, King Mulawarman’s generosity towards the Brahmins is commemorated.

King Mulawarman’s father, Acwawarman, was the founder of the royal dynasty and it seems likely that the Brahmins referred to in the inscriptions were Agnihotrins, followers of the Veda, a branch of Hinduism. Nothing is known about Kutei for the next 1,000 years.

In 1365, we find the name Kutai mentioned in the old-Javanese historical poem Nigarakrtggama, verse 14.1. It is also around this time the Kingdom of Kutai begins to form. Kutai probably annexed four areas, Djahitan-Lajar, Hulu-Dusun, Sembaran and Binalu. After 1606 and the beginning of Islam, more regions were taken including Markam, Kota Bangun and Pahu.

The genealogical line of the Kutai dynasty begins with Batara Agung Maharadja Dewa Sakti as the first Sultan of Kutai and ends with Adji Mohammed Parikesit, the 20th Sultan, who still lives at Tenggarong. (1971)

In 1635, 1671 and 1673 Dutch adventurers visited the area but no further contact was made. Samarinda was found in 1730. In 1825 an agreement was reached with the Sultan of Kutai but did not last. During the first half of the 19th century trade with the English commenced and Singapore became the centre for goods from Kutai.

Before the arrival of H. von Dewall the first Dutch administrator on the east coast of Borneo, power was in the hands of the Sultan and his immediate family. This power was executed along the Mahakam River and its branches. The jurisdiction of the sultan ceased officially at Gunung Sendawar, a small hill. The Sultan was forbidden to travel beyond the hill.

The power of the Sultans was economic rather than political or religious. It was founded on the toll bridge. At Tenggarong on the Mahkam, the sultan had his residence and he collected river tolls, where duties were imposed on all incoming and outgoing merchandise. The revenues from this taxation benefited the Sultan and his family and no portion went to benefit any social welfare institution. Other sources of income included opium and salt and gambling.

When a Sultan dies, his oldest legitimate son, the Pangeran Ratu, succeeds to the throne. When the heir to the throne is under age, then the oldest brother of the deceased King is named regent with the title Pangeran Mangku Putra. In the event, the Sultan has no brothers, the head of the Mangu Sukma becomes regent. Where the oldest son of a concubine, and becomes Putra Sukma, ineligible for the throne.

For a long time, the Buginese enjoyed a singular status in Kutai. Coming from the Celebes, they established themselves in 1700 in what is now Samarinda, spreading through all of Kutai. During the 1700’s they operated unchecked. They were subject to their own Pau Adu, elected by the kepala manang or the heads of the Buginese families of the state. However, an elected man could be vetoed by the Sultan

When Sultan Mohammed Caliudin died in July 1845, the political order collapsed. The seven-year-old Sultan became a pawn in the power struggle. The perdana manteri (the head manteri negri) became the regent. He allowed the regency to fall resulting in widespread anarchy and lawlessness. Criminals were no longer prosecuted, robbery and arson were daily occurrences and were employed by the princes. Pirates from Balingingi, Tongka and Tarakan plagued the east coast and the slave trade flourished.

When J. Zwager was appointed the Assistant Resident by the Dutch, the manteri negri informed him they could do nothing about the prevailing anarchy. When the Sultan became of age in 1863, the Dutch signed a treaty with him and declared that the Kingdom of Kutai was part of the Dutch East India Company and belonged to the Sultan only as a fief. Peace and order were restored by the Dutch.

In 1900 the Sultan ceded the right to impose these taxes to the Dutch government in exchange for 105,000 Dutch guilders. This arrangement allowed the Dutch to virtually destroy the economic domination the Sultan had over his people. At the same time, the Dutch acknowledged the position of the Sultan who now was responsible for administrative affairs.

The Sultan was now assisted by four or five manteri-negri (great officers of State, with whom he sat in the bali (council chambers) for bidjara (consultations.) The manteri-negri held the title of pangeran which was an appointive rather than a hereditary title. The Sultan was the highest judge in the manner of religion. However, in 1924 he passed those duties to the manteri negri who then became Hakim Mahakamah Islam and judged religious cases assisted by other the manteri negri.

Because of Sultan’s many wives and concubines, the royal family grew large in time and the matter of their financial support became an acute problem. Many of Sultan’s relatives were directly supported by the Sultan. Other relatives established themselves and their followers further from the river and employed their time in feuding, gambling and terrorizing the local population. The Sultan was powerless to put an end to this situation because he was unable to enforce his rule far from the Gunang Sedewar.

The worst abuses subsided or disappeared in 1900 with the arrival of the civil administrator Barth. The Sultans were more than willing to allow the Dutch to look after their country’s interests as long as it did not affect them. The real power was now in the hands of the Dutch.

Titles were always cheap in Kutai. However, the 19th century saw the indiscriminate awarding that titles became meaningless. There were hardly any standards or norms. The most important titles were tumenggung, raden, demang and kiahi. The pembekels were the village heads.

The headman’s task was upholding local adat. The headmen have little power. He was not permitted to act on his own in the name of the village. The community was responsible and liable as a whole. The power of the village headman was used by the Dutch. The village headman was reduced to enforcing the edicts of the Dutch.

In Kutai, in former times, judgements were pronounced by the adat book of laws, Beradja Nanti. The Chairman of these courts were appointed and dismissed by the Sultan. There seems to have been a second book of laws in use, one for the aristocracy, in which the penalties were milder than in the Beradja Nanti. This book fell into disuse as the laws of the Dutch were applied.

The Sultanate of Kuti, Kalimantan Timur: A sketch of the Traditional Structure by J.R. Wortmann Borneo Research Bulletin December 1971, Milestones in the History of Kutai by J.R. Wortmann Borneo Research Bulletin June 1971

BorneoHistory.net